-

(#5) The More Spice, The Better

When it came to fine dining in the Middle Ages, nothing was a more ostentatious show of privilege and wealth than the amount of spices used when cooking. Because of the great lengths it took to import highly sought spices like saffron, ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, and cloves from the Middle East and Asia, only the extremely rich could afford to cook with rich flavors in mind. For instance, a pound of saffron cost as much as a horse. During banquets at the homes of the well-off, a spice plate was passed around so the guests might sample the rare and exciting flavors.

Salt was among the most prized of seasonings, and was even kept locked away by the master or mistress of the house. The phrase "below the salt" (meaning of low status) comes from the table settings at medieval banquets; lords and their families were seated with access to salt while they dined, while guests of less import and servants were seated below it.

-

(#9) Their Plates Were Literally Bread

Two imperative modern pieces of tableware might not be present at a medieval foodie's table: the fork and the plate. Anything not edible with a spoon would be placed upon a piece of dry, coarse bread called a "trencher" and eaten by hand. They were generally about three days old and very hard and stale.

In lower-class households, folks might not have had trenchers at all; they would simply eat their food straight off of the table itself. For the upper crust, however, the various sauces and juices of the meats would soak into the hollowed-out bread throughout the meal. While it was acceptable to eat the trencher after the meal had come to a close, most chose to give their soggy leftovers to the servants or the poor as alms.

-

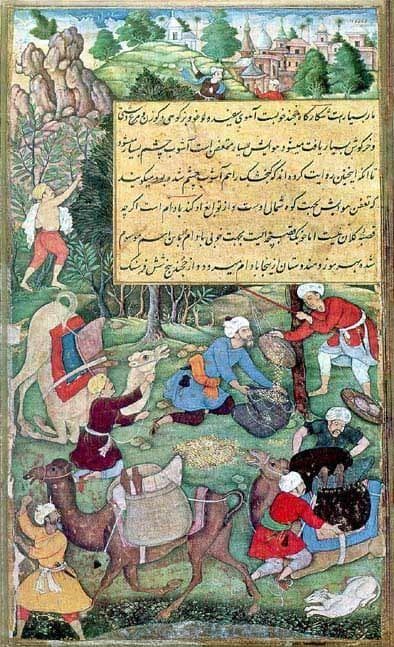

(#3) Feasts Included Meat, Meat, And More Meat

Medieval gourmets ate a lot of different animals - rabbits, cows, pigs, goats, fowls, sheep, deer, and boars, just to name a few. Even hedgehogs and porcupines sometimes ended up on plates. A single banquet menu once consisted of a veritable zoo of creatures, with 12 pigeons, 12 chickens, six rabbits, two herons, a whole deer, a sturgeon, a pig, and a kid goat appearing in just three of the massive six courses. Some feasts may have included a roast boar stuffed with sausages that would pour out of its belly when the beast was carved.

Pies were often seen on the table among other roasted and stewed meats, containing layer upon layer of pigeon, rabbit, or pork. The sometimes intricately decorated crust on the outside was usually not intended to be eaten and existed to keep the meaty insides fresh and protected. The truly discerning palate would prefer only fresh meat as opposed to salted, preserved cuts. However, no animal parts went to waste, including the bladder, stomach, and womb of the pig, which were often used as sausage casing.

-

(#10) Meals Were Sweetened With Jellies And Candied Fruits

A dessert course as we know it wouldn’t have been common at a medieval banquet; meats, cheeses, and fish were often served alongside sweets, for instance. However, candied confections appeared sprinkled throughout feasts. Fruits were a common treat for noble diners, especially pears, and were served covered in honey or sugar by the late Middle Ages. Sweet pottages decorated with flower petals were often served, but the jewel-colored jellies truly won the hearts of guests.

There are records of fantastical jellies molded in the shapes of animals and castles, and rosewater-flavored delicacies at the garter feast of Henry VIII. This type of aspic was made from the rendering of animal bones and cartilage, and was often set with crayfish, eggs, and other savory bits. Setting the multicolored jellies in a checkerboard pattern was a favorite technique of chefs.

-

(#6) Fruits And Veggies Had To Be Cooked

Life in the Middle Ages was really filthy. As such, raw fruits and vegetables could easily make a person terribly ill - if not worse. The Boke of Kervynge cautions chefs: "Beware of green sallettes and rawe fruytes for they wyll make your soverayne seke," meaning green salads could even take the life of the master of the house. Any noble's garden was stocked with a variety of fresh vegetables and herbs that were used both for cooking and curing ailments.

It was not uncommon at all to cook fruits together with fish, eggs, and meat, but vegetables were sometimes passed over by the elite of the Middle Ages. They were commonly consumed by, and thus associated with, the lower classes. The dietitians of nobility regarded legumes, particularly, with some disdain because they are liable to cause flatulence.

-

(#4) Rich Pottage Stew Was A Mainstay

Pottage was a staple of medieval cuisine, and appeared at nearly every banquet. This hearty stew often showed up around the first course of a feast. The mixture was a hodge-podge of grains, bits of meat, egg yolks, and seasonal vegetables like cabbage or spinach.

Chefs would boil the pottage for hours until all the ingredients became as one. It was usually served with ale, wine, and bread, with the finest loaves being reserved for the elites. This stew mainly acted as an appetizer for the rich gourmands of the Middle Ages.

New Random Displays Display All By Ranking

About This Tool

The feasts of the Middle Ages is similar to the modern dinner party in some ways. They light up candles, then serve soup and salad, then taste better food, and desserts. The more formal or special occasion, the more luxurious. Medieval nobles were obsessed with exotic delicacies, such as the swans at Henry VIII's dinner. It should be known that guests are also subject to various etiquette rules in the medieval feast.

Do you dream you could travel back to Medieval time? There are some details about the glorious medieval feast, you could check the generator if you are interested in. Welcome to search for others that you like with the tool.

Our data comes from Ranker, If you want to participate in the ranking of items displayed on this page, please click here.