-

(#5) Death Was Like A Performance

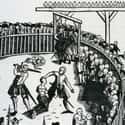

When you became an executioner, you knew it was not only about ridding the world of sinners. As with the teachings of the Church, there were still imperative lessons. In your time, public executions had to accomplish two distinct goals. First of all, you wanted to shock spectators and use the harrowing scene as a preventive measure.

The second goal was to buttress and reaffirm divine and temporal authority. As executioner, you played a pivotal role in achieving this delicate balance. You staged the events - from condemnation through death procession to the actual execution - all as if it were a play.

Indeed, the people of your era were familiar with “morality plays.” These were allegorical dramas where characters had personified moral qualities (such as charity or vice) or abstractions (as death or youth), complete with a moral lesson. What greater stage performance to present these ideas publicly than by executing a sinner?

The "good death" Meister Franz Schmidt... sought was essentially a drama of religious redemption, in which the poor sinner acknowledged and atoned for his or her crimes, voluntarily served as an admonitory example, and in return was granted a swift death and the promise of salvation. It was, in that sense, the last transaction a condemned prisoner would make in this world.

You fulfilled your goal of addressing the divine and earthly realms on the state’s behalf through this ritualized and regulated brutality.

-

(#7) The Show Must Go On

Though he had already confessed to his crime, you present Vogel to the “blood court,” where his sentence will become known. You watch the red and black-robed judges in the ornately decorated room.

You listen as the scribe reads the final confession and its tally of offenses, concluding with the formulaic condemnation: “Which being against the laws of the Holy Roman Empire, my Lords have decreed and given sentence that he shall be condemned from life to death by...” The jurors pause to vote on the manner of execution: by rope, sword, fire, water, or the wheel. They choose the sword.

To present this living morality play to as many people as possible, broadsheets circulated weeks in advance. This assured hundreds - and maybe thousands - of onlookers. Vogel must walk a mile to reach his place of execution. His journey is without incident.

This is not always the case, though. You lament when a prisoner behaves wildly or gives trouble. You sharply recall one unruly drunkard who urinated in the open at the gallows. When he learned his sentence, he said he was willing to die, but asked as a favor to fence and fight four of the guards. As you wrote in your journal, “His request was refused.”

-

(#1) Some Days There Might Be Multiple Executions, But Today There Is Just One

The stereotypical image of a 16th-century executioner is of a burly, bare-chested fellow in a black hood, wielding a massive axe. This mask may send shivers down the spines of kids today, but the town executioner was likely proud of his well-paying job.

For other executioners across Europe, sometimes they had several victims to deal with in the same day. If you lived in the time of Henry VIII, you hardly had time for a break - there are estimates of as many as 72,000 executions during Henry’s reign.

You would have had your day cut out for you, so to speak. But this time, your task is different. Today, on August 13, 1577, you have but one execution before you. You will not behead bands of pirates or break the bones of your victims on the wheel. Your charge is a man named Hans Vogel, and your duty: Send this repentant sinner off to the promise of salvation.

-

(#6) The Last Meal Could Be A Feast Or Famine

It’s common knowledge the condemned man can request whatever he wants for his last meal. The condemned could order whatever he or she wanted, and in copious amounts - wine and beer included. Of course, imbibing large quantities of spirits at the “hangman’s meal” were often to the advantage of the executioner.

The prisoner was occasionally dead-drunk and nonresistant before actually dying. In one instance, a rogue consumed so much food and drink his stomach had burst as he swung from the gallows. No doubt you also witnessed those prisoners who would not touch a bite.

Once Vogel finishes his meal, your assistants clothe him in a white linen execution gown. Attired in his earthly shroud, he awaits you to preside over the public spectacle to come. The warden announces you with the customary words: “The executioner is at hand.” Dressed in your ceremonial best, you enter and ask Vogel for forgiveness. You then share the traditional drink of peace with him. After a few words, you move on to the waiting judge and jury.

-

(#8) Three Strikes Of The Blade Or The Executioner Is Out, Too

During your 45-year career and 187 recorded executions with the sword, you required a second stroke only four times. This is impressive, but you knew the consequences of a shoddy beheading all too well. In some German towns, it was three strikes and you’re out - that is, an executioner could have three strikes of the blade before the crowd grabbed them and forced them to die in place of the condemned prisoner.

Crowds often comprised drunkards ready to riot at the drop a hat, especially when there wasn't the drop of a head. The riots could turn bloody. You dispatch Vogel with one clean swipe. In answer to the judge’s satisfaction with your work, you reply, “For that I thank God and my master who has taught me such art.”

Finally there is the mundane task of mopping up. The performance is not over until you clean up the blood and dispose of the dead man. The mob lingers in morbid curiosity until you're done.

After your retirement in 1617, you begin a new, lucrative career as a medical consultant. More accurately, you resume your other job. Harrington calculated the number of patients seeking medical advice amounted to roughly 15,000. You received a state funeral in 1634, in Nuremberg’s most prominent cemetery.

Your burial site is only a few paces away from the graves of the famous painter Albrecht Dürer and poet Hans Sachs. And you did it all without once wearing a hood.

-

(#3) Executioners And Prisoners Often Became Acquainted

As is customary with prisoners, you've gotten to know Vogel - after all, you are personally sending him off to eternity. If he had serious wounds or were otherwise ill, you would have nursed him back to health, fulfilling the duties of your secondary profession as a medical consultant.

You might have also requested the execution's delay so he could face a proper death with his health intact. You must have thought it fitting “vogel” meant bird, and if he were truly repentant, he would have assuredly ascended to heaven.

It was not uncommon for prisoners like Vogel to receive visitors, such as family members or the relatives of the victim seeking reconciliation. You knew deep down: Forgiveness is divine, and you must've felt joyful when one condemned killer accepted some oranges and gingerbread from his victim’s widow. You saw it as a sign that she had wholeheartedly forgiven him.

You also might contemplate your role as someone who metes out justice in the name of society and - above all - God. It is your professional and sacred duty to serve as an agent who balances divine and earthly authority.

New Random Displays Display All By Ranking

About This Tool

Many people think that the executioners in the Middle Ages in Europe were ruthless people wearing masks and carrying an ax, killing people without blinking, but in fact, this is an illusion of the image of the executioner. In the 16th century, top executioners were also excellent doctors, and they probably saved more people than they killed. The real medieval executioner is a profession that was misunderstood and discriminated against but plays a key role.

In the 16th century, Europe was turbulent and the public security situation was poor. All countries were working hard to improve the criminal law enforcement situation. The executioner was particularly important. The random tool introduced 8 details about what it was like to be a medieval executioner.

Our data comes from Ranker, If you want to participate in the ranking of items displayed on this page, please click here.